#240519 ~ CONTEXT, ECONOMY, CEREMONY

Brian Eugenio Herrera's #TheatreClique Newsletter for May 19, 2024.

WELCOME to #TheatreClique — my (mostly) weekly newsletter dedicated to encouraging you to click out to some of the most interesting, intriguing & noteworthy writing about drama, theatre & performance (at least, so says me)…

This Week's #TheatreCliquery:

For this week’s opener, I lift this video in which actor, drag performer, and “Queen of All Queens” Jinkx Monsoon introduces her newly “earnest” rendition of a song that’s long been part of her repertoire…

EDITOR’S NOTE: whenever possible, whenever linking to paywalled pieces, I “gift” the article to #TheatreClique readers. In other words, clicking out to articles in the New York Times, Washington Post, Atlantic, and Wall Street Journal should neither present hassle nor burn through your monthly allotment of free views. Here’s hoping more outlets — hello LATimes! hi ChicaoTribune! yo NewYorker!— adopt similar technologies for subscribers soon...

#NowClickThis…

Wherein I highlight a dozen or so of the most click-worthy links I’ve encountered in the last few weeks…

V Magazine’s Savannah Sobrevilla listens in as actors Jinkx Monsoon and Cole Escola chat about how “their lives have intersected very randomly” and the delights/hazards of annoying theatre audiences with “queer stupidity”;

at Vogue, theatre writer Juan A. Ramírez gives an illuminating glimpse into what it was like to attend twelve Broadway opening “nights” in nine days;

at LinkedIn, immersive experience designer Joanna Garner puts Meow Wolf’s (huge) recent round of layoffs in essential context;

The New York Times’s Cade Metz digs into a lawsuit brought by voice actors against an AI start-up for “cloning” their voices;

American Theatre’s Rob Weinert-Kendt talks to Kristin Marting (the founding artistic director of the influential HERE Arts Center) about the past, the future, and whether the arts can survive in this economy”;

TheatreMania’s Zachary Stewart considers its perhaps premature Broadway closing as “not the end for Lempicka — just the beginning of a long exile”;

at The Atlantic, Chris Heath talks to actor Daniel Radcliffe about about “doing theater for half his life now, and [how] onstage was where he made his first bold break from expectations” of Harry Potter;

at The Washington Post, critic/commentator Elisabeth Vicentelli assesses how the current spate of Hollywood stars on Broadway actually did;

The New Yorker’s Parul Seghal talks to MaryJane playwright Amy Herzog about having audiences “enter into the strangeness of caregiving”;

The Nation’s D.D. Guttenplan talks to Gillian Slovo about bringing her verbatim drama about survivors of London’s Grenfell Tower fire to New York;

at Vanity Fair, theatre commentator/writer Michael Riedel considers the enduring power (and relevance) of Cabaret;

at The New York Times, author/scholar James Shapiro traces some of the historical context undergirding the recent spate of attacks on theater in American schools;

at American Theatre, writer/editor Billy McEntee profiles 86-year-old Nicki Cochrane, whose “tireless” theatregoing has made her a minor legend and a peculiarly persistent problem (especially for front-of-house staff) across the NYC theatre circuit;

at The New York Times, writer/editor Kim Hew-Low evinces how televisual dramaturgy permeates TikTok storytelling;

and tireless theatre tiktoker Kate Reinking launches first The Creators’ Choice Awards for the Broadway 2023-24 season!

And Lest I Forget — This Week in FERRER-iana…

Wherein I depart somewhat from my own Fornésian tradition to highlight noteworthy recent or upcoming engagements with the life, work and legacy of a legendary Latine theatremaker who is not María Irene Fornés...

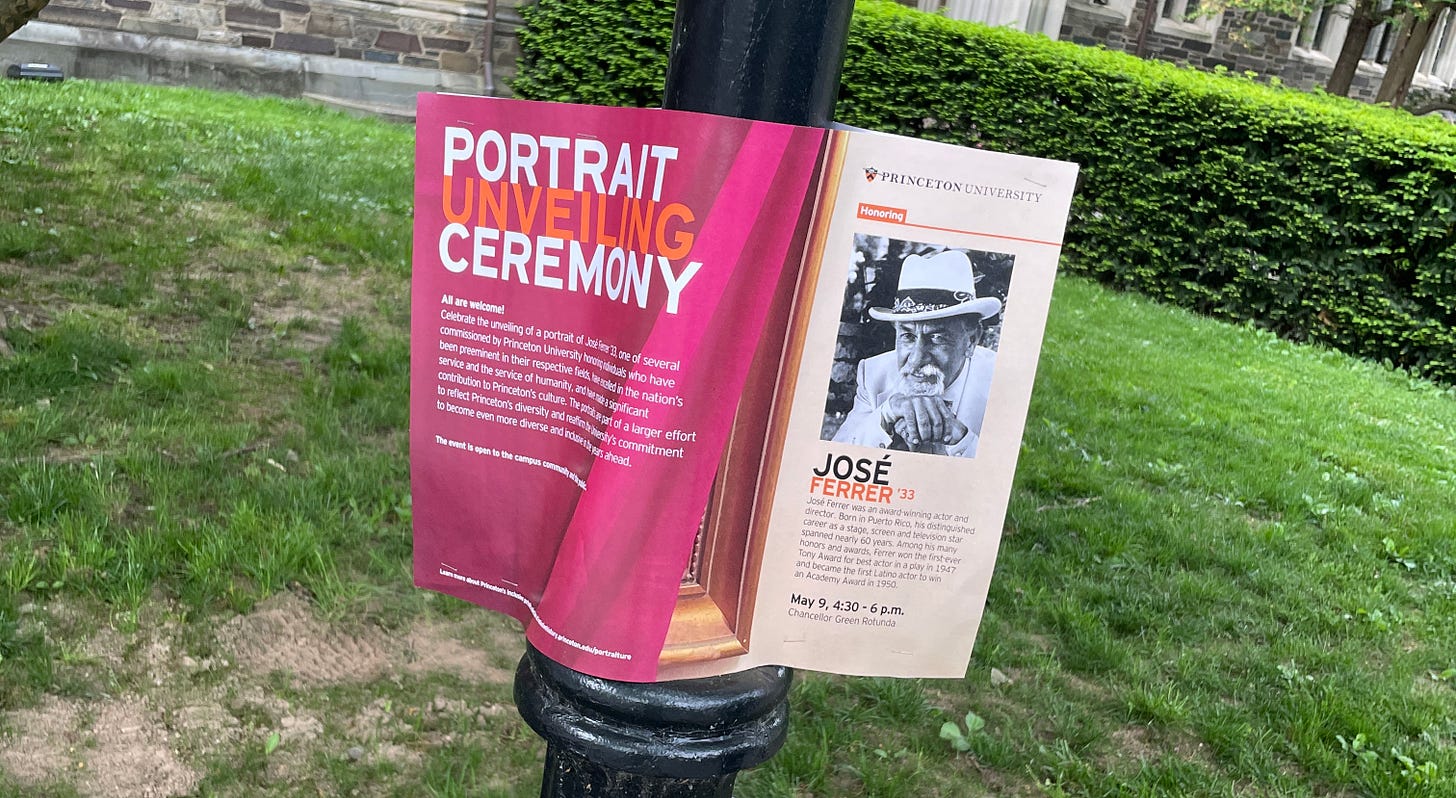

A week or so ago, I was invited to participate in a new-to-me campus ritual: an “unveiling ceremony” of a piece of art commissioned by my university to be displayed on campus as part of Princeton’s History and Sense of Place Initiative. Because of my persistence (aka “nagging”) in nominating José Ferrer PU’33 as an apt candidate for campus portraiture, I was invited to speak at the ceremony. Jamie Saxon offers a more comprehensive account of the event on the Princeton homepage; below, you will find my very lightly revised remarks in full.

It's an honor to be with you today and to share why I’m so excited that a portrait of José Ferrer will soon hang in Princeton's Lewis Center for the Arts, where I am a member of the faculty.

As I was developing my first book – Latin Numbers: Playing Latino in Twentieth Century Popular Performance – I dug deep into the professional and personal biographies of about two dozen twentieth century stage and screen actors we might today recognize as Latina, Latino, or Latine.

José Ferrer stood prominently among them, as not only a revered and path-breaking actor, but also noteworthy as a director, a writer, a producer, an advocate for the arts, and – in particular – as a champion for the arts as a platform to engage the most consequential social issues of the day.

My final revisions for the book happened during my first few years at Princeton which might be what stirred my interest in how José Ferrer's multifaceted constellation of artistic skills and commitments manifested during his time as Princeton student.

A favorite José Ferrer factoid I've never had the opportunity to share publicly came, in my first year or two at Princeton, when I arranged for the students in one of my classes to take a tour of Princeton’s Mudd Library. As we wandered the aisles of bound theses representing the independent senior work of prior generations of Princeton students, archivist Daniel Linke asked if we might like to see the thesis of any particular Princeton alum. By acclamation, the students all wanted to see Sonia Sotomayor's but I asked for José Ferrer's. I don't recall the topic – perhaps something to do with French naturalism? – but I do remember smiling as I read the comments of José Ferrer's thesis advisor, who chided the young Ferrer for not dedicating the same measure of time to his academic thesis as he did to his efforts on campus stages.

I was moved by this professor's mildly snarky comment... mostly for how it anchored Ferrer in the long genealogy of student performance-makers at Princeton who struggle – in varying measure – to balance their deeply felt artistic commitments both within and beyond the classroom.

Perhaps that’s why I find it so fitting that Ferrer's portrait will hang at the Lewis Center for the Arts. To my mind, few of Princeton's many distinguished arts alumni so aptly embody how the performing arts have long thrived at Princeton, through an intricate balance of the rigor of curricular study and the excitement of co-curricular and extra-curricular experimentation.

Ferrer's blessing and burden – his being so passionately multifaceted in both his talents and commitments – deeply aligns with the experience of Princeton arts students today. For, long before we had the term “multi-hyphenate” artist, José Ferrer embodied the particular challenge of being a socially-engaged and defiantly interdisciplinary artist-scholar.

Indeed, the early 1950s, Ferrer signed an "all-embracing contract" with Twentieth Century-Fox that allowed him to work in movies, television, and theater, both as an actor and as a director. Nearly unprecedented not just in its day but for the entirety of the twentieth century, Ferrer's bespoke contract stands as just one of the many history-making features of Ferrer's career.

Mostly famously perhaps, in 1950, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (or the Oscars) named Puerto Rican actor José Ferrer the year’s “Best Actor” for his performance as the title character in Cyrano de Bergerac. It was not his first Oscar nod, for he had been nominated two years before for his supporting performance in Joan of Arc. Nor was the Oscar his first award for the role of Cyrano, because he also won the Tony for his Cyrano performance on Broadway in 1947. Even so, Ferrer’s recognition as Best Actor marked the first (and, to date, ONLY) time Oscar so awarded an actor of Latin American heritage. Indeed, in the 95-year history of the Academy Awards, Ferrer remains the only Latine actor to have won the Oscar in the leading actor or actress category. (Ferrer also remains the only Latine performer to be awarded the Tony as Best Actor in a Play.)

But just two years after his Oscar win for Cyrano, Ferrer returned to the Broadway stage where he earned the rare distinction of winning two Tony Awards – his first as director and second as actor – for his work in that year's Pulitzer Prize winning play The Shrike. Ferrer's directing Tony also cited his achievement in also directing two other plays that season– the romantic drama The Fourposter and the prisoner-of-war drama Stalag 17… (Directing three plays on Broadway, while acting in one, in a single season? Sounds like something a Princeton student artist would do…)

Ferrer's accumulation of awards in the early 1950s followed a prodigious period of post-grad professional activity. Notably, in 1943, Ferrer co-starred opposite Princeton-born Paul Robeson in the first Broadway production of Shakespeare's Othello to feature an African American actor in the title role. (The production ran for nearly 300 performances, setting the still-standing record for the longest-running Shakespeare play on Broadway.)

Two years later, In 1945, Ferrer directed the Broadway premiere of the hotly anticipated stage adaptation of Strange Fruit, Lillian Smith’s best-selling novel of interracial romance. The production starred rising actor/director (and José’s Princeton classmate) Melchor Ferrer. Cuban American Mel Ferrer and Puerto Rican José Ferrer shared no filial relation but had become acquainted at Princeton, where Mel’s elder brother—also named José—happened to be one of two José Ferrers graduating in the class of 1933.

The six decades of his post-Princeton career chart Ferrer’s sustained commitment to socially consequential art across film, television, and theatre. Consider how, in 1980, José Ferrer directed an arch social satire by Nuyorican activist/artist Pedro Pietri (sometimes called the "Poet Laureate of the Young Lords") in a tiny New York theatre dedicated to Latino arts and culture. That same year, Ferrer starred on national television opposite Henry Fonda in a critically-acclaimed made-for-tv historical drama Gideon's Trumpet about the supreme court case that confirmed the right-to-counsel for defendants without the ability to pay.

Such juxtapositions are many in the career of José Ferrer. Which is why I’m so glad for the prompt that this portrait — by New Jersey-based Puerto Rican artist Luis Alvarez Roure — will provide to the Princeton student artists of today…

This portrait will hang as an open prompt to not only to learn more about José Ferrer’s extraordinary life and work and also to remind us all that — long before there was a Lewis Center for the Arts – that there were defiantly interdisciplinary, socially-engaged student artists discovering their paths at Princeton… students like José Vicente Ferrer de Otero y Cintrón, one of the two José Ferrers in the great class of 1933.